Mulch volcanoes are NOT good

Mulching your landscape trees and shrubs can potentially kill if done improperly. A recent and serious trend has been over-mulching landscape plants, also called mulch volcanoes. Not only is over-mulching a waste of mulch, (and a potentially costly one at that), it is rapidly becoming the number one cause of death to shrubs and trees.

One of the most common causes of stress by over-mulching is suffocation of plant roots. Repeated applications of mulch can contribute to a waterlogged soil and root zone by slowing soil water loss through evaporation. Roots must respire (breathe) and take in oxygen, unlike leaves which give off oxygen. When oxygen levels in the soil drop below 10 percent, root growth declines. When too many roots decline and die, the plant will eventually succumb.

Symptoms of Tree Damage From Over-Mulching

- off-color foliage

- abnormally small leaves

- poor twig growth

- die-back of older branches

It is most important to remember that the problems caused from yearly over-mulching are not immediate, but progress slowly with time. The symptoms may take 3 – 5 years to express themselves and sometimes longer, depending on the species and sod type. Unfortunately, by the time the symptoms are recognized it’s generally too late to apply corrective measures. At this point, the plant has usually gone into an irreversible decline and will most likely die.

A second major cause of plant decline and death from over-mulching comes from the piles of mulch being placed against the stems of trees and shrubs. The above ground stem and trunk tissue is very different from root tissues. Roots have evolved many mechanisms to survive in continually moist environments, the trunks of most woody species have not. Above ground stems must be able to freely exchange adequate amounts of oxygen and carbon dioxide through lenticels. When mulch is piled onto the trunks, gas exchange decreases with phloem tissue eventually becoming stressed and later dying. When the phloem dies, roots are malnourished and weakened to the point where they suffer reduced water and nutrient uptake, which subsequently affects the health of the whole plant.

A third mortality factor which is associated with the application of mulching next to stem tissue involves fungal and bacterial diseases. Most plant diseases require moisture to grow and reproduce. Trunk diseases are no exception and will usually gain entry into the stressed, decaying bark tissue caused by the homeowners unknowingly piling the mulch next to the tree trunk. Once established, even secondary fungal invaders such as Phytophthora and Armillaria species will eventually kill the inner bark, thereby starving the roots, and ultimately killing the plant. Many times, bark beetles and borers (which are also attracted to the stressed trees) will assist in the decline of the tree and allow other fungal pathogens entrance into the tree. This has been observed with clearwinged borers which normally attack higher on the stem.

Excess heat can also be generated when wet mulch layers placed up against the stem begin to decompose. Similar to composting where inner mulch layers may reach 120° to 140° F., the heat may kill young tree and shrub phloem, or, may prevent the natural hardening off process plants must go through to prepare themselves for winter.

The continuous use of the same type of mulch may also contribute to plant stress by ultimately changing the soil’s acidity level, commonly referred to as soil pH. Acid mulches like pine bark may have a pH of 3.5 to 4.5 and when applied year in and year out, may cause the soil to become too acid to grow many alkaline requiring plants. Due to the increased solubility of many micronutrients in acid soil, toxic levels of nucronutrients may lead to additional plant stress which in turn allows secondary pathogens and insects to invade. Conversely, hardwood bark mulch, which is initially acidic, may cause the soil to eventually become too basic or alkaline causing acid loving plants to quickly decline because of micronutrient deficiencies. Soil pH’s above 6.5 – 7.0 usually create micronutrient deficiencies of iron, manganese, and zinc for many common, acid-loving, landscape plants. Small changes in soil acidity can be avoided by periodically monitoring soil pH and rotating the type of mulch used.

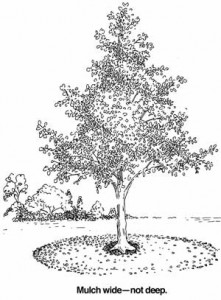

Mulch should not be touching the trunk and trunk flare should be visible

Placing piles of mulch adjacent to tree trunks can also kill plants by providing cover and habitat for chewing rodents such as small mice, meadow voles, etc.. With lots of cover from predators, the rodents will usually live under the warm mulch in the winter and chew on the tender and nutritious inner bark to get at the sugars. This chewing off of the bark many times goes unnoticed until the following spring or summer when the tree doesn’t look good. If the chewing is extensive or goes around the whole tree, there is little that can be done to save the tree. Bridge grafting with strips of bark over the girdled area can be done but is time consuming and most arborists are not willing to go to those extremes.

Finally, many fresh or non-aged mulches may cause nitrogen deficiencies in young trees, shrubs, and flowers. Decomposing bacteria and fungi which ultimately break down mulch must have an ample supply of nitrogen to do their job. Most landscaping mulches are comprised of bark or wood which have high carbon to nitrogen ratios and have very little nitrogen available for the decomposing bacteria. Hence, the bacteria in the soil utilize the existing nitrogen to break down the mulch. This process may cause nitrogen deficiencies on new growth. Although nitrogen deficiencies may occur, they are usually considered temporary as the mulch will eventually release its nutrients into the soil and the decomposition will taper off.

Allelopathic mulches are mulches which contain toxic elements which will inhibit the growth of other plants. These toxic chemicals can be produced in the leaves, roots, trunk, or fruit of some plants and will slow the growth of some plants and in some cases, kill the competing plant. The classic case of allelopathy found in nature is the black walnut. This species along with other close relatives produce the toxic chemical juglone and juglonic acid which inhibits the growth of many trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants. Juglone is found in all parts of the plant including leaves, twigs, trunk and roots. Hence, fresh wood chips and sawdust should not be used as a mulch unless adequately composted and even then, small amounts of juglone can be detected. Besides Black Walnut, other allelopathic mulches include sawdust of Redwood and Red Cedar and the bark of Spruce, Larch and Douglas Fir. All of these materials may reduce root growth and deform or kill some trees and shrubs. Evergreen bark sometimes releases toxic volatile gases that can be especially harmful to plants including tomatoes and other vegetable crops as well. To neutralize the allelochems found in these toxic species, compost the mulch with nitrogen at two pounds of actual nitrogen per cubic yard of mulch.

How Much Mulch Should I Use?

If you have shallow rooted species and those species are growing on somewhat poorly drained soil, mulch depths should not exceed a 2 inch depth. For perpetually wet soils which need as much oxygen as possible, it may be more advisable to control weeds with a combination of a systemic post-emergent herbicide and pre-emergent herbicide such as Round-Up and Surflan herbicides.

On the other hand, if you have more deeply rooted species growing on well drained loams or sandy soils, your plants would benefit from a 2-4 inch depth of mulch. With coarser textured mulches you can go a bit deeper due to the better oxygen diffision through the mulch and ‘into the soil. Be more cautious with the finer, doubleshredded mulches on the market. A 2 inch layer may be all you need to keep weeds down and prevent unnecessary soil drying in the summer.

The best way to determine if you have a problem with excessive mulch piling in your landscape is to go out and simply dig through the mulch layer to see how thick it really is. A light raking of the existing mulch is all that is needed to break up any crusted or compacted mulch layers that can repel water and to give it that finished landscape appearance. As a rule-of-thumb, keep the mulch a minimum of 3 – 6 inches away from the trunks of young trees and shrubs and 8 – 12 inches away from mature tree trunks.

What Can Be Done If My Trees Were Over-Mulched?

Conducting a visual inspection of the root flare is the best way for an arborist to check a tree or shrub for a possible root collar disorder. If no root flare or buttress roots are found, the chances are good that at least some of the root crown has been buried. When burial is suspected, the arborist must first carefully probe downward to determine the extent and depth of burial. If the root collar is buried, you must remove the soil or mulch below the surface of the Junction of the roots and the trunk collar (without damaging the roots or collar) to expose the root collar. This is necessary to allow the collar to dry out and begin respiration of essential oxygen and carbon dioxide.

Arborists may also take a small strip of bark and sapwood from the root collar following excavation to determine the presence of fungal pathogens such as Phytophthora or Armillaria species. The resulting exposed well must be left open unless the root collar disorder is so severe that the resultant tree decline or hazard potential warrants tree removal.

According to tree expert scientists, an amazing number of plants have improved rapidly in color and vigor within months of a root collar excavation. Observations also indicate far less winter injury in such plants because the healthy roots, once an excavation has been conducted, produce the growth regulators responsible for above ground winter hardiness.

Of course, pruning of any dead and or dying branches should be conducted to reduce the introduction and spread of disease in treated trees. A light fertilization with a low salt index, slowrelease, nitrogen fertilizer (at 1 – 2 pounds of actual nitrogen per 1000 square feet) may also be required of trees treated for root collar disorders to renew vitality and growth.

In summary, over-mulching and root collar burial is needlessly killing many landscape trees and shrubs by oxygen starvation of the roots, lack of gas exchange and death of inner bark, promoting stem and root diseases, prevention of hardening off via increased mulch temperatures and declining root vigor, rodent girdling, development of water repelling mulch layers, allelopathic mulches, potential short-term nitrogen deficiencies, and nutrient and acidity problems from sour mulch.

Fortunately, most of these problems can easily be prevented with periodic inspections.